Figure 24.1. Female seahorses produce eggs for reproduction that are then fertilized by the male. Unlike almost all other animals, the male seahorse then gestates the young until birth. (credit: modification of work by “cliff1066″/Flickr)

Introduction

Animal reproduction is necessary for the survival of a species. In the animal kingdom, there are innumerable ways that species reproduce. Asexual reproduction produces genetically identical organisms (clones), whereas in sexual reproduction, the genetic material of two individuals combines to produce offspring that are genetically different from their parents. During sexual reproduction the male gamete (sperm) may be placed inside the female’s body for internal fertilization, or the sperm and eggs may be released into the environment for external fertilization. Seahorses, like the one shown in Figure 24.1, provide an example of the latter. Following a mating dance, the female lays eggs in the male seahorse’s abdominal brood pouch where they are fertilized. The eggs hatch and the offspring develop in the pouch for several weeks.

Reproduction Methods

Animals produce offspring through asexual and/or sexual reproduction. Both methods have advantages and disadvantages. Asexual reproduction produces offspring that are genetically identical to the parent because the offspring are all clones of the original parent. A single individual can produce offspring asexually and large numbers of offspring can be produced quickly. In a stable or predictable environment, asexual reproduction is an effective means of reproduction because all the offspring will be adapted to that environment. In an unstable or unpredictable environment asexually-reproducing species may be at a disadvantage because all the offspring are genetically identical and may not have the genetic variation to survive in new or different conditions. On the other hand, the rapid rates of asexual reproduction may allow for a speedy response to environmental changes if individuals have mutations. An additional advantage of asexual reproduction is that colonization of new habitats may be easier when an individual does not need to find a mate to reproduce.

During sexual reproduction the genetic material of two individuals is combined to produce genetically diverse offspring that differ from their parents. The genetic diversity of sexually produced offspring is thought to give species a better chance of surviving in an unpredictable or changing environment. Species that reproduce sexually must maintain two different types of individuals, males and females, which can limit the ability to colonize new habitats as both sexes must be present.

Asexual Reproduction

Asexual reproduction occurs in prokaryotic microorganisms (bacteria) and in some eukaryotic single-celled and multi-celled organisms. There are a number of ways that animals reproduce asexually.

Fission

Fission, also called binary fission, occurs in prokaryotic microorganisms and in some invertebrate, multi-celled organisms. After a period of growth, an organism splits into two separate organisms. Some unicellular eukaryotic organisms undergo binary fission by mitosis. In other organisms, part of the individual separates and forms a second individual. This process occurs, for example, in many asteroid echinoderms through splitting of the central disk. Some sea anemones and some coral polyps (Figure 24.2) also reproduce through fission.

Figure 24.2. Coral polyps reproduce asexually by fission. (credit: G. P. Schmahl, NOAA FGBNMS Manager)

Budding

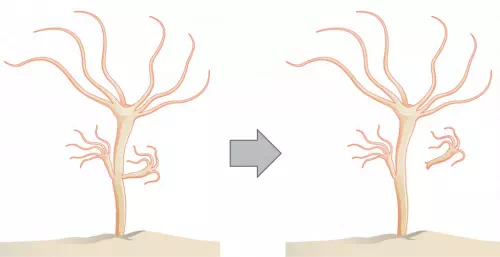

Budding is a form of asexual reproduction that results from the outgrowth of a part of a cell or body region leading to a separation from the original organism into two individuals. Budding occurs commonly in some invertebrate animals such as corals and hydras. In hydras, a bud forms that develops into an adult and breaks away from the main body, as illustrated in Figure 24.3, whereas in coral budding, the bud does not detach and multiplies as part of a new colony.

Figure 24.3. Hydra reproduce asexually through budding.

Fragmentation

Fragmentation is the breaking of the body into two parts with subsequent regeneration. If the animal is capable of fragmentation, and the part is big enough, a separate individual will regrow.

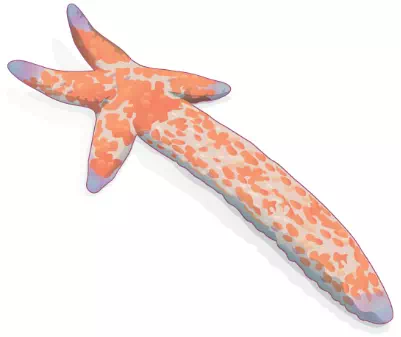

For example, in many sea stars, asexual reproduction is accomplished by fragmentation. Figure 24.4 illustrates a sea star for which an arm of the individual is broken off and regenerates a new sea star. Fisheries workers have been known to try to kill the sea stars eating their clam or oyster beds by cutting them in half and throwing them back into the ocean. Unfortunately for the workers, the two parts can each regenerate a new half, resulting in twice as many sea stars to prey upon the oysters and clams. Fragmentation also occurs in annelid worms, turbellarians, and poriferans.

Figure 24.4. Sea stars can reproduce through fragmentation. The large arm, a fragment from another sea star, is developing into a new individual.

Note that in fragmentation, there is generally a noticeable difference in the size of the individuals, whereas in fission, two individuals of approximate size are formed.

Parthenogenesis

Parthenogenesis is a form of asexual reproduction where an egg develops into a complete individual without being fertilized. The resulting offspring can be either haploid or diploid, depending on the process and the species. Parthenogenesis occurs in invertebrates such as water flees, rotifers, aphids, stick insects, some ants, wasps, and bees. Bees use parthenogenesis to produce haploid males (drones) and diploid females (workers). If an egg is fertilized, a queen is produced. The queen bee controls the reproduction of the hive bees to regulate the type of bee produced.

Some vertebrate animals—such as certain reptiles, amphibians, and fish—also reproduce through parthenogenesis. Although more common in plants, parthenogenesis has been observed in animal species that were segregated by sex in terrestrial or marine zoos. Two female Komodo dragons, a hammerhead shark, and a blacktop shark have produced parthenogenic young when the females have been isolated from males.

Comments are closed.