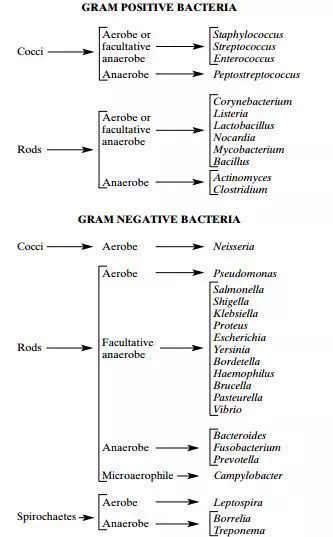

Gram staining method, the most important procedure in Microbiology, was developed by Danish physician Hans Christian Gram in 1884. Gram staining is still the cornerstone of bacterial identification and taxonomic division.

This differential staining procedure separates most bacteria into two groups on the basis of cell wall composition:

1. Gram-positive bacteria (thick layer of peptidoglycan-90% of cell wall)- stains purple

2. Gram-negative bacteria (thin layer of peptidoglycan-10% of cell wall and high lipid content) –stains red/pink

Image 1: Basic classification of Medically Important Bacteria

Nearly all clinically important bacteria can be detected/visualized using Gram staining method the only exceptions being those organisms;

1. That exists almost exclusively within host cells i.e. Intracellular bacteria (e.g., Chlamydia)

2. Those that lack a cell wall (e.g., Mycoplasma)

3. Those of insufficient dimensions to be resolved by light microscopy (e.g., Spirochetes)

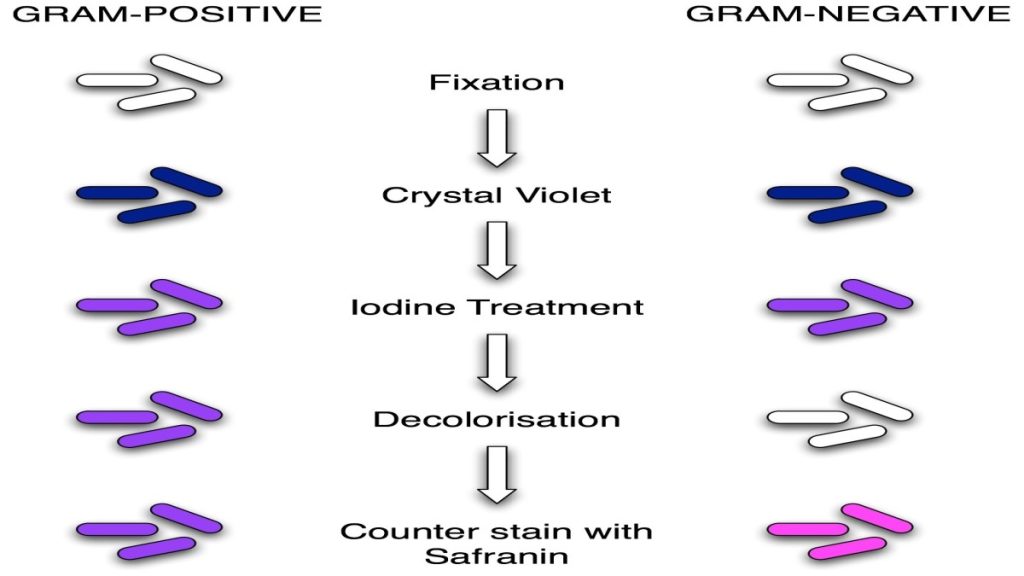

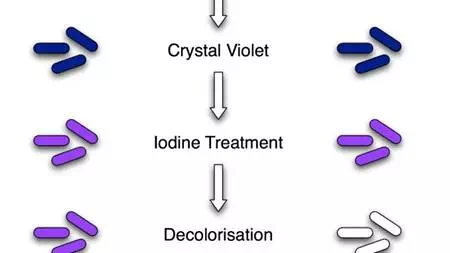

Classic Gram staining techniques involve the following steps:

1. Fixation of clinical materials to the surface of the microscope slide either by heating or by using methanol. (# Methanol fixation preserves the morphology of host cells, as well as bacteria, and is especially useful for examining bloody specimen material).

An easy way to remember the steps of the Gram stain

2. Application of the primary stain (crystal violet). Crystal violet stains all cells blue/purple

3. Application of mordant: The iodine solution (mordant) is added to form a crystal violet-iodine (CV-I) complex; all cells continue to appear blue.

4. Decolorization step: The decolorization step distinguishes gram-positive from gram-negative cells.

The organic solvent such as acetone or ethanol, extracts the blue dye complex from the lipid-rich, thin-walled gram-negative bacteria to a greater degree than from the lipid-poor, thick-walled, gram-positive bacteria. The gram-negative bacteria appear colorless and gram-positive bacteria remain blue.

5. Application of counterstain (safranin): The red dye safranin stains the decolorized gram-negative cells red/pink; the gram-positive bacteria remain blue.

Find information and process for the Preparation of Gram Staining Regent

Principle of Gram Stain

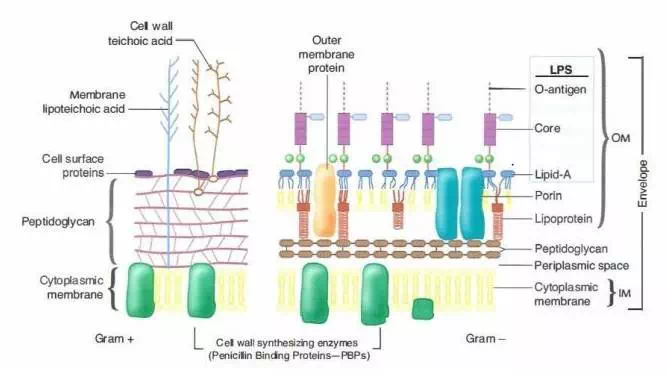

Image 2: Cell wall of Gram Positive and Gram Negative Bacteria

The differences in cell wall composition of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria account for te Gram staining differences. Gram-positive cell wall contains a thick layer peptidoglycan with numerous teichoic acid cross-linking which resists the decolorization. In aqueous solutions, crystal violet dissociates into CV+ and Cl – ions that penetrate through the wall and membrane of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative cells. The CV+ interacts with negatively charged components of bacterial cells, staining the cells purple.

When added, iodine (I- or I3-) interacts with CV+ to form large crystal violet-iodine (CV-I) complexes within the cytoplasm and outer layers of the cell. The decolorizing agent, (ethanol or an ethanol and acetone solution), interacts with the lipids of the membranes of both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. The outer membrane of the Gram-negative cell (lipopolysaccharide layer) is lost from the cell, leaving the peptidoglycan layer exposed. Gram-negative cells have thin layers of peptidoglycan, one to three layers deep with a slightly different structure than the peptidoglycan of gram-positive cells. With ethanol treatment, gram-negative cell walls become leaky and allow the large CV-I complexes to be washed from the cell.

The highly cross-linked and multi-layered peptidoglycan of the gram-positive cell is dehydrated by the addition of ethanol. The multi-layered nature of the peptidoglycan along with the dehydration from the ethanol treatment traps the large CV-I complexes within the cell. After decolorization, the gram-positive cell remains purple in color, whereas the gram-negative cell loses the purple color and is only revealed when the counterstain, the positively charged dye safranin, is added.

Smear Preparation

Fix material on a slide with methanol or heat. If the slide is heat fixed, allow it to cool to the touch before applying the stain.

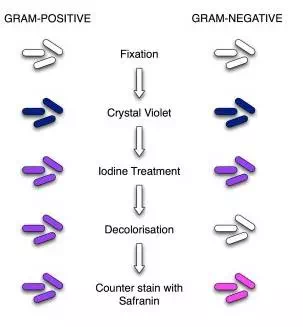

Image 3: Procedure of Gram Staining; note the color change after each step

Gram Staining Procedure/Protocol:

1. Flood air-dried, heat-fixed smear of cells for 1 minute with crystal violet staining reagent. Please note that the quality of the smear (too heavy or too light cell concentration) will affect the Gram Stain results.

2. Wash slide in a gentle and indirect stream of tap water for 2 seconds.

3. Flood slide with the mordant: Gram’s iodine. Wait 1 minute.

4. Wash slide in a gentle and indirect stream of tap water for 2 seconds.

5. Flood slide with decolorizing agent (Acetone-alcohol decolorizer). Wait 10-15 seconds or add drop by drop to slide until decolorizing agent running from the slide runs clear.

6. Flood slide with a counterstain, safranin. Wait 30 seconds to 1 minute.

7. Wash slide in a gentile and indirect stream of tap water until no color appears in the effluent and then blot dry with absorbent paper.

8. Observe the results of the staining procedure under oil immersion (100x) using a Bright field microscope.

Results:

· Gram-negative bacteria will stain pink/red and

· Gram-positive bacteria will stain blue/purple.

Reporting Gram smears

The report should include the following information:

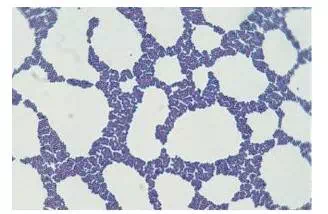

Staphylococcus in Gram Stain

§ Numbers of bacteria present, whether many, moderate, few, or scanty

§ Gram reaction of the bacteria, whether Gram positive or Gram negative

§ Morphology of the bacteria, whether cocci, diplococci, streptococci, rods, or coccobacilli. Also, whether the organisms are intracellular.

§ Presence and number of pus cells

§ Presence of yeast cells and epithelial cells.