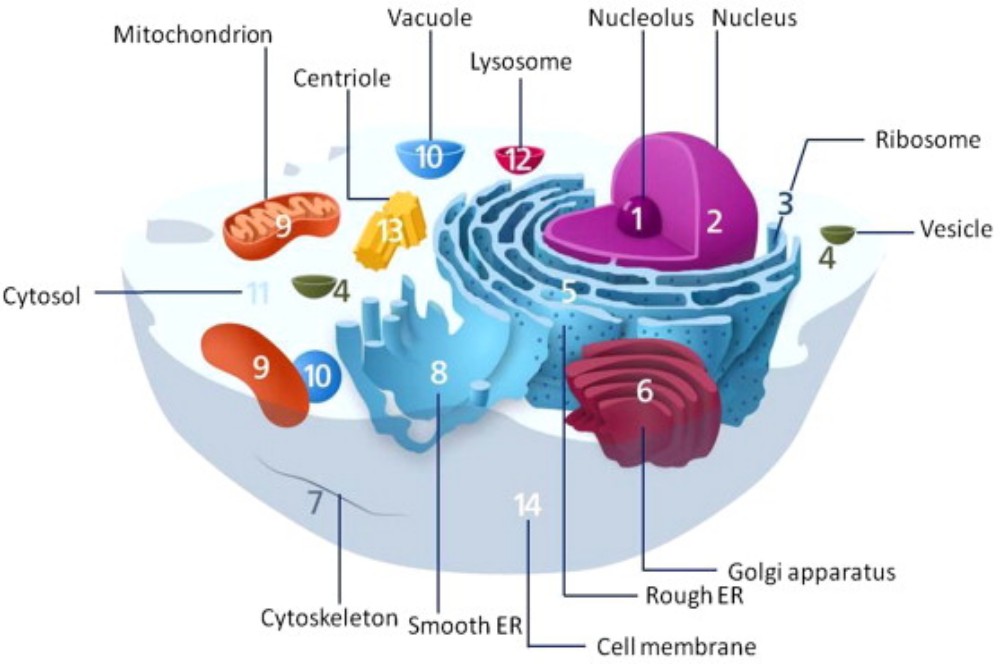

The endomembrane system (endo = within) is a group of membranes and organelles in eukaryotic cells that work together to modify, package, and transport lipids and proteins. It includes the nuclear envelope, lysosomes, vesicles, endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi apparatus, which we will cover shortly. Although not technically within the cell, the plasma membrane is included in the endomembrane system because, as you will see, it interacts with the other endomembranous organelles.

The Nucleus

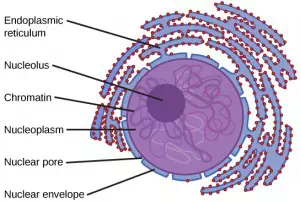

Typically, the nucleus is the most prominent organelle in a cell. The nucleus (plural = nuclei) houses the cell’s DNA in the form of chromatin and directs the synthesis of ribosomes and proteins. Let us look at it in more detail (Figure 3.11).

Figure 3.11 The outermost boundary of the nucleus is the nuclear envelope. Notice that the nuclear envelope consists of two phospholipid bilayers (membranes)—an outer membrane and an inner membrane—in contrast to the plasma membrane ([link]), which consists of only one phospholipid bilayer. (credit: modification of work by NIGMS, NIH)

The nuclear envelope is a double-membrane structure that constitutes the outermost portion of the nucleus (Figure 3.11). Both the inner and outer membranes of the nuclear envelope are phospholipid bilayers.

The nuclear envelope is punctuated with pores that control the passage of ions, molecules, and RNA between the nucleoplasm and the cytoplasm.

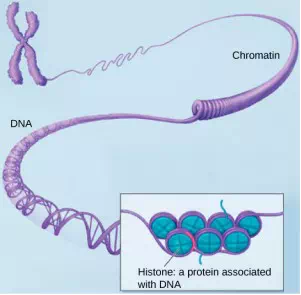

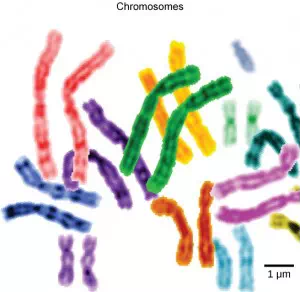

To understand chromatin, it is helpful to first consider chromosomes. Chromosomes are structures within the nucleus that are made up of DNA, the hereditary material, and proteins. This combination of DNA and proteins is called chromatin. In eukaryotes, chromosomes are linear structures. Every species has a specific number of chromosomes in the nucleus of its body cells. For example, in humans, the chromosome number is 46, whereas in fruit flies, the chromosome number is eight.

Chromosomes are only visible and distinguishable from one another when the cell is getting ready to divide. When the cell is in the growth and maintenance phases of its life cycle, the chromosomes resemble an unwound, jumbled bunch of threads.

Figure 3.12 This image shows various levels of the organization of chromatin (DNA and protein).

Figure 3.13 This image shows paired chromosomes. (credit: modification of work by NIH; scale-bar data from Matt Russell)

We already know that the nucleus directs the synthesis of ribosomes, but how does it do this? Some chromosomes have sections of DNA that encode ribosomal RNA. A darkly stained area within the nucleus, called the nucleolus (plural = nucleoli), aggregates the ribosomal RNA with associated proteins to assemble the ribosomal subunits that are then transported through the nuclear pores into the cytoplasm.

The Endoplasmic Reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a series of interconnected membranous tubules that collectively modify proteins and synthesize lipids. However, these two functions are performed in separate areas of the endoplasmic reticulum: the rough endoplasmic reticulum and the smooth endoplasmic reticulum, respectively.

The hollow portion of the ER tubules is called the lumen or cisternal space. The membrane of the ER, which is a phospholipid bilayer embedded with proteins, is continuous with the nuclear envelope.

The rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER) is so named because the ribosomes attached to its cytoplasmic surface give it a studded appearance when viewed through an electron microscope.

The ribosomes synthesize proteins while attached to the ER, resulting in the transfer of their newly synthesized proteins into the lumen of the RER where they undergo modifications such as folding or addition of sugars. The RER also makes phospholipids for cell membranes.

If the phospholipids or modified proteins are not destined to stay in the RER, they will be packaged within vesicles and transported from the RER by budding from the membrane. Since the RER is engaged in modifying proteins that will be secreted from the cell, it is abundant in cells that secrete proteins, such as the liver.

The smooth endoplasmic reticulum (SER) is continuous with the RER but has few or no ribosomes on its cytoplasmic surface. The SER’s functions include synthesis of carbohydrates, lipids (including phospholipids), and steroid hormones; detoxification of medications and poisons; alcohol metabolism; and storage of calcium ions.

The Golgi Apparatus

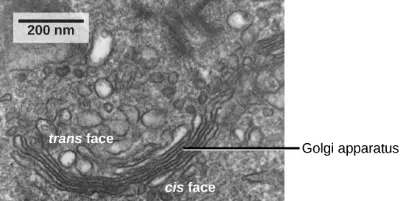

We have already mentioned that vesicles can bud from the ER, but where do the vesicles go? Before reaching their final destination, the lipids or proteins within the transport vesicles need to be sorted, packaged, and tagged so that they wind up in the right place. The sorting, tagging, packaging, and distribution of lipids and proteins take place in the Golgi apparatus (also called the Golgi body), a series of flattened membranous sacs.

Figure 3.14 The Golgi apparatus in this transmission electron micrograph of a white blood cell is visible as a stack of semicircular flattened rings in the lower portion of this image. Several vesicles can be seen near the Golgi apparatus. (credit: modification of work by Louisa Howard; scale-bar data from Matt Russell)

The Golgi apparatus has a receiving face near the endoplasmic reticulum and a releasing face on the side away from the ER, toward the cell membrane. The transport vesicles that form from the ER travel to the receiving face, fuse with it, and empty their contents into the lumen of the Golgi apparatus. As the proteins and lipids travel through the Golgi, they undergo further modifications. The most frequent modification is the addition of short chains of sugar molecules. The newly modified proteins and lipids are then tagged with small molecular groups to enable them to be routed to their proper destinations.

Finally, the modified and tagged proteins are packaged into vesicles that bud from the opposite face of the Golgi. While some of these vesicles, transport vesicles, deposit their contents into other parts of the cell where they will be used, others, secretory vesicles, fuse with the plasma membrane and release their contents outside the cell.

The amount of Golgi in different cell types again illustrates that form follows function within cells. Cells that engage in a great deal of secretory activity (such as cells of the salivary glands that secrete digestive enzymes or cells of the immune system that secrete antibodies) have an abundant number of Golgi.

In plant cells, the Golgi has an additional role of synthesizing polysaccharides, some of which are incorporated into the cell wall and some of which are used in other parts of the cell.