Although all of Mendel’s pea plant characteristics behaved according to the law of independent assortment, we now know that some allele combinations are not inherited independently of each other. Genes that are located on separate, non-homologous chromosomes will always sort independently. However, each chromosome contains hundreds or thousands of genes, organized linearly on chromosomes like beads on a string. The segregation of alleles into gametes can be influenced by linkage, in which genes that are located physically close to each other on the same chromosome are more likely to be inherited as a pair. However, because of the process of recombination, or “crossover,” it is possible for two genes on the same chromosome to behave independently, or as if they are not linked. To understand this, let us consider the biological basis of gene linkage and recombination.

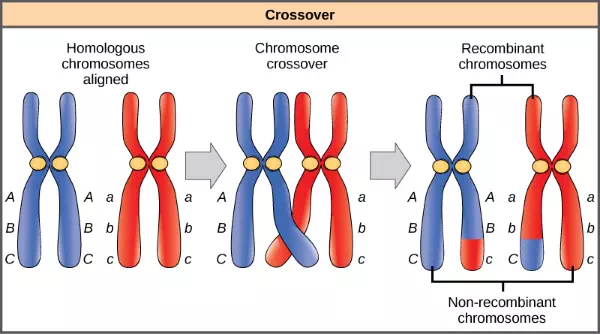

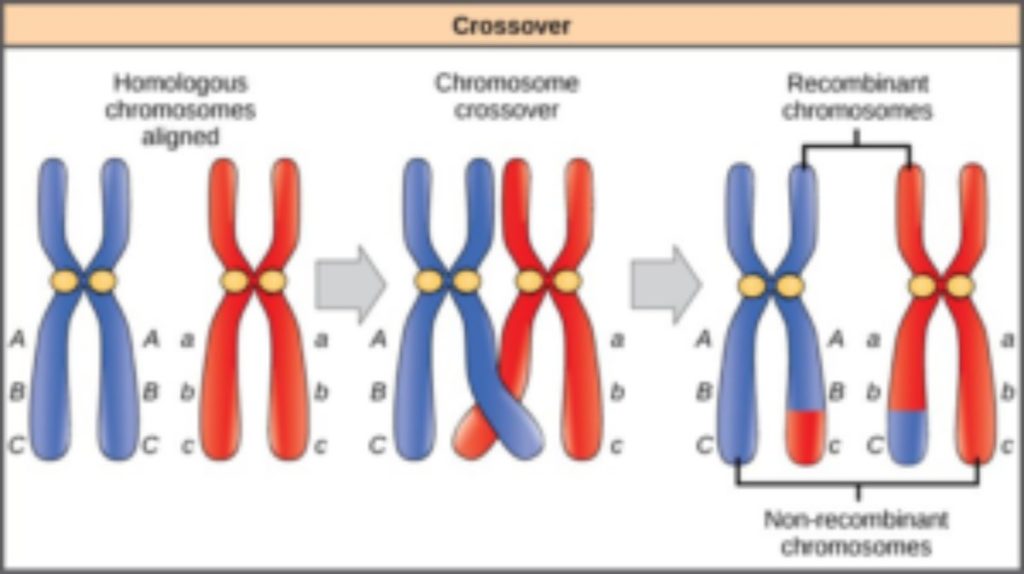

Homologous chromosomes possess the same genes in the same order, though the specific alleles of the gene can be different on each of the two chromosomes. Recall that during interphase and prophase I of meiosis, homologous chromosomes first replicate and then synapse, with like genes on the homologs aligning with each other. At this stage, segments of homologous chromosomes exchange linear segments of genetic material (Figure 8.18). This process is called recombination, or crossover, and it is a common genetic process. Because the genes are aligned during recombination, the gene order is not altered. Instead, the result of recombination is that maternal and paternal alleles are combined onto the same chromosome. Across a given chromosome, several recombination events may occur, causing extensive shuffling of alleles.

Figure 8.18 The process of crossover, or recombination, occurs when two homologous chromosomes align and exchange a segment of genetic material.

When two genes are located on the same chromosome, they are considered linked, and their alleles tend to be transmitted through meiosis together. To exemplify this, imagine a dihybrid cross involving flower color and plant height in which the genes are next to each other on the chromosome. If one homologous chromosome has alleles for tall plants and red flowers, and the other chromosome has genes for short plants and yellow flowers, then when the gametes are formed, the tall and red alleles will tend to go together into a gamete and the short and yellow alleles will go into other gametes. These are called the parental genotypes because they have been inherited intact from the parents of the individual producing gametes. But unlike if the genes were on different chromosomes, there will be no gametes with tall and yellow alleles and no gametes with short and red alleles. If you create a Punnett square with these gametes, you will see that the classical Mendelian prediction of a 9:3:3:1 outcome of a dihybrid cross would not apply. As the distance between two genes increases, the probability of one or more crossovers between them increases and the genes behave more like they are on separate chromosomes. Geneticists have used the proportion of recombinant gametes (the ones not like the parents) as a measure of how far apart genes are on a chromosome. Using this information, they have constructed linkage maps of genes on chromosomes for well-studied organisms, including humans.

Mendel’s seminal publication makes no mention of linkage, and many researchers have questioned whether he encountered linkage but chose not to publish those crosses out of concern that they would invalidate his independent assortment postulate. The garden pea has seven chromosomes, and some have suggested that his choice of seven characteristics was not a coincidence. However, even if the genes he examined were not located on separate chromosomes, it is possible that he simply did not observe linkage because of the extensive shuffling effects of recombination.

Comments are closed