Organization and Development of the Immune System

The immune system is a wonderful collaboration between cells and proteins that work together to provide defense against infection. These cells and proteins do not form a single organ like the heart or liver. Instead, the immune system is dispersed throughout the body to provide rapid responses to infection (Figure 1). Cells travel through the bloodstream or in specialized vessels called lymphatics. Lymph nodes and the spleen provide structures that facilitate cell-to-cell communication.

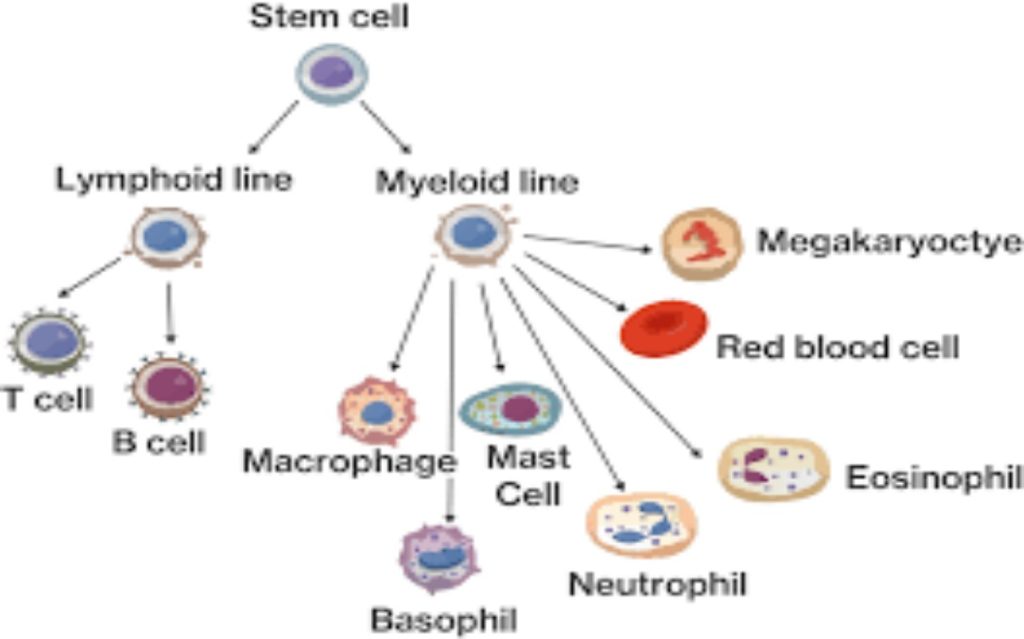

The bone marrow and thymus represent training grounds for two cells of the immune system (B-cells and T-cells, respectively). The development of all cells of the immune system begins in the bone marrow with a hematopoietic (blood-forming) stem cell (Figure 2). This cell is called a “stem” cell because all the other specialized cells arise from it. Because of its ability to generate an entire immune system, this is the cell that is most important in a bone marrow or hematopoietic stem cell transplant. It is related to embryonic stem cells, but is a distinct cell type. In most cases, development of one cell type is independent of the other cell types.

Primary immunodeficiencies can affect only a single component of the immune system or multiple cells and proteins. To better understand the immune deficiencies discussed later, this section will describe the organization and maturation of the immune system.

Although all components of the immune system interact with each other, it is typical to consider two broad categories of immune responses: the innate immune system and the adaptive immune system.

Innate immune responses are those that rely on cells that require no additional “training” to do their jobs. These cells include neutrophils, monocytes, natural killer (NK) cells and a set of proteins termed the complement proteins. Innate responses to infection occur rapidly and reliably. Even infants have excellent innate immune responses.

Adaptive immune responses comprise the second category. These responses involve T-cells and B-cells, two cell types that require “training” or education to learn not to attack our own cells. The advantages of the adaptive responses are their long-lived memory and the ability to adapt to new germs.

Central to both categories of immune responses is the ability to distinguish foreign invaders (things that need to be attacked) from our own tissues, which need to be protected. Because of their ability to respond rapidly, the innate responses are usually the first to respond to an “invasion.” This initial response serves to alert and trigger the adaptive response, which can take several days to fully activate.

Early in life, the innate responses are most prominent. Newborn infants do have antibodies from their mother but do not make their own antibodies for several weeks.

The adaptive immune system is functional at birth, but it has not gained the experience necessary for optimal memory responses. Although this formation of memory occurs throughout life, the most rapid gain in immunologic experience is between birth and three years of age. Each infectious exposure leads to training of the cells so that a response to a second exposure to the same infection is more rapid and greater in magnitude.

Over the first few years of life, most children catch a wide variety of infections and produce antibodies directed at those specific infections. The cells producing the antibody “remember” the infection and provide long-lasting immunity to it. Similarly, T-cells can remember viruses that the body has encountered and can make a more vigorous response when they encounter the same virus again. This rapid maturation of the adaptive immune system in early childhood makes testing young children a challenge since the expectations for what is normal change with age. In contrast to the adaptive immune system, the innate immune system is largely intact at birth.

Major Organs of the Immune System

A. Thymus: The thymus is an organ located in the upper chest. Immature lymphocytes leave the bone marrow and find their way to the thymus where they are “educated” to become mature T-lymphocytes.

B. Liver: The liver is the major organ responsible for synthesizing proteins of the complement system. In addition, it contains large numbers of phagocytic cells which ingest bacteria in the blood as it passes through the liver.

C. Bone Marrow: The bone marrow is the location where all cells of the immune system begin their development from primitive stem cells.

D. Tonsils: Tonsils are collections of lymphocytes in the throat.

E. Lymph Nodes: Lymph nodes are collections of B-lymphocytes and T-lymphocytes throughout the body. Cells congregate in lymph nodes to communicate with each other.

F. Spleen: The spleen is a collection of T-lymphocytes, B-lymphocytes and monocytes. It serves to filter the blood and provides a site for organisms and cells of the immune system to interact.

G. Blood: Blood is the circulatory system that carries cells and proteins of the immune system from one part of the body to another.