Up until James Watson and Francis Crick’s experiments, we had very little understanding of exactly what made living things look and appear as they do. Other models had been proposed, but Watson and Crick believed that these models were inferior for numerous reasons that we’ll not get into here. Their own model became the basis for our concept of DNA and helped unlock the genetic code of all living things.

In 1953, Francis Crick and James Watson developed what would be henceforth known as the Watson and Crick Model of DNA, which supposes that DNA exists in a double-helical twisted ladder structure of phosphate chains with matching nucleotides. DNA, as we well know, stands for deoxyribonucleic acid and is the backbone or blueprints for all life as we understand it.

Basis for the Model

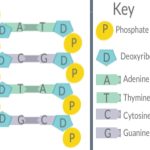

Prior to Watson and Crick, it was understood that there was a blueprint for all life and that this blueprint consisted of nucleotides and phosphate strands. Throughout the late 1800s and into the early 1900s advances had been made in finding this blueprint, but nothing as concrete as what was to come. Watson and Crick were able to determine that the four nucleotides contained in DNA (cytosine, guanine, thymine, and adenine) would only pair up in certain ways: adenine to thymine, guanine to cytosine. They had borrowed this idea from Erwin Chargaff, and they also ran with a helical theory proposed by Rosalind Franklin, whose photographs of DNA gave them a basis from which to start. Unfortunately, Franklin was not asked permission to see the photos and was also not credited for her contribution in the discovery.

Comments are closed